Crack is whack! Above the influence! Use, and you lose! The echoes of childhood propaganda which tried to scare us straight.

We’re kids of the “Just Say No” generation, the abstinence-only approach to drug use trumpeted by then First Lady Nancy Reagan while her husband was busy slashing funds for vulnerable populations such as the poor and mentally ill.

Remember the sizzle of our eggy brains in the frying pan? Or the meth addict’s terrifying house-cleaning jingle? What about the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles cooly reminding us, “Drug dealers are dorks!”—a cartoon ironically spawned by heavy marijuana users, or at least individuals with highly dissociative thinking. The War on Drugs even coopted our beloved cast of Saved by the Bell—“There’s no hope with dope!”—after Jessie freaked out having ingested too many caffeine pills. We were continually reminded by everyone from our parents to the lovable Scruff McGruff—D.A.R.E.’s anti-drug cartoon canine—that drugs are baaaaad and we’d inevitably be sticking syringes in our little arms if we tried one puff of Mexican skunk weed.

So I ask you: In the years since these PSAs hit the airwaves, what has happened to us Millennials?

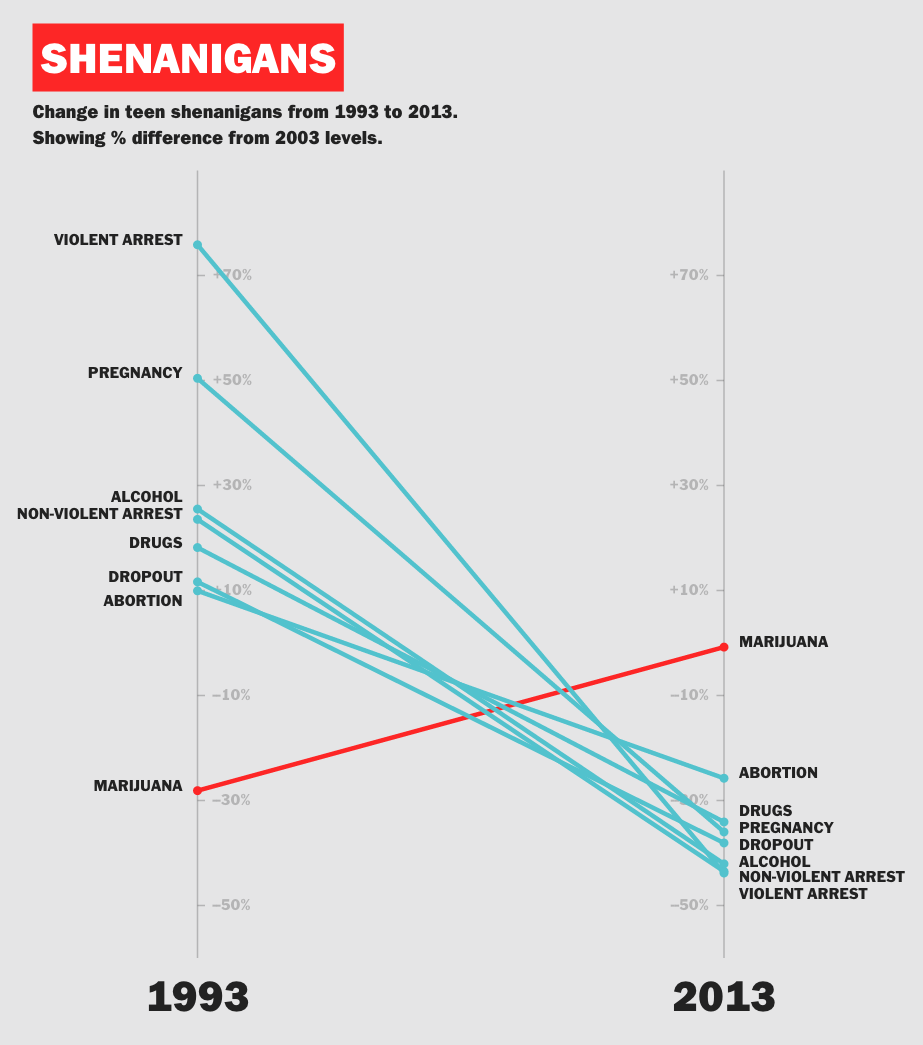

Well, the ads worked (or something did—Roe v. Wade and less unwanted babies being born, perhaps?—a discussion beyond the scope of this article). Illicit drug use, alcohol abuse, cigarette smoking, and a slew of other negative social indicators (e.g., teenage pregnancy, crime rates, dropouts, etc.) among Millennials are much lower than in previous generations. Vocativ (2015)—pulling data from the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), the National Institute on Drug Abuse, and the Department of Justice—illustrates just how well-behaved our Generation Y has been:

So what’s the problem here?

Two things, actually. First, I believe that our understanding of addiction is flat and selectively demonizes groups with less power in society. Second, I think that PSAs have been targeting the wrong perpetrators, that over the past few decades, much more insidious drug-peddlers have hooked Americans across all generations. And these pushers don’t operate from the shadows, but rather sell their dope openly, on TV even. I’m talking about something that kills more people annually than car crashes, something that kills more people than all illicit drugs combined. I’m talking about good ol’ corporate, doctor-prescribed narcotics.

I’ll begin by qualifying my position. I worked as an addiction specialist for over two years at a non-profit methadone clinic in San Francisco. I managed a caseload of roughly 50 people who had been (or still were) heroin-users. Methadone—an opioid that occupies the same brain receptors as heroin but without the same sedation or euphoria—is the pharmaceutical equivalent of kicking the can down the road. In essence, it replaces one substance with another, but most importantly it allows people to live stable, normal lives. Without the threat of withdrawals, they can maintain jobs, take care of their families, and go on about their business.

I was struck by the fact that some of my clients were just like me—young, ambitious, from loving families—and were a far cry from the grotesque “Faces of Addiction” we’ve seen pop-up in our Facebook feeds. Where were the festering blisters on their faces? Where were the signs that they were not to be trusted under any circumstances? What was heartbreaking is that my clients—mainly respectful and civic-minded individuals—had an acute awareness of society’s appalling concept of an “addict” and were self-conscious about it. Many had done time in prison for the non-violent crime of having a disease, and the shame of having been addicted to heroin dripped from their stories, as if they were trying to atone for having fallen off one of society’s most jagged edges. It reminded me that our concept of addiction is weighed heavily against lower income groups such as the homeless and minorities, groups with comparatively less power in society.

It’s incredibly ironic that the War on Drugs and the subsequent mass incarceration of non-violent offenders—a policy that continues to disproportionately affect poor and minority people—was ignited by President Nixon, a notorious alcoholic. And I wonder how we would view addiction differently if PSAs had been created in the image of the rich and powerful addict?

Here’s what I mean:

- Show us the Wall Street executive snorting lines of uncut Columbian off his mahogany desk and believing he’s invincible before rolling the dice with your grandmother’s stock portfolio.

- Show us the bored, bony, Bel Air housewife who exercises for three hours a day and spends her weekly allowance from her overworked, philandering husband on a daily bottle of Veuve Clicquot while Maria or Svetlana raises her kids.

- Show us the flush-faced politician who writes scathing polemics about drug-users while nursing his OxyContin addiction in a gated community. (Ahem, Rush Limbaugh.)

- Show us the 22-year-old marketing manager in New York who blacks out every weekend on $15 cosmos and can no longer achieve orgasm unless she’s on mollie.

- Show us the lead engineer in the Silicon Valley tech firm who pops Ritalin to code all night and keep up with the increasing demands of his employer.

- Show us the millions of Americans who turn to sugary, fatty, comfort food—treats that were marketed to them on TV—to iron out life’s little speed bumps and then ask their doctors about one-pill solutions to their subsequent obesity, high cholesterol, high blood pressure, acid reflux, and heart ailments.

The point is that there’s always been an element of privilege to our concept of addiction. Poor addicts provoke contempt and disgust, while hard-partying wealthy addicts inspire TV specials and book deals. It’s all very unfair as we’re sold the bogeyman of “the marginalized other”—the dirty, disgruntled addict—to distract us from our own troubling habits nurtured by powerful forces.

This phenomena is intimately connected with my second argument. I believe that the biggest perpetrators of addiction, disease, and death are not the drugs that PSAs warned us about, but rather legally prescribed medications.

It’s no secret that the U.S. government has a cozy relationship with Big Pharma. Time (2015) writes a telling exposé on the new Deputy Commissioner of the FDA, Dr. Robert Califf, who believes that the U.S. needs less regulation in the development of new drugs, including the loosening of the approval process and a slackening of the post-market oversight. Given the number of drugs and devices that are recalled annually after causing serious injuries and death (e.g., Vioxx, Phen-fen, Propulsid, Zyprexa), and given the number of multimillion (and multibillion) dollar lawsuits annually, how can one of the top regulators of the FDA—an organization meant to safeguard the public interest—believe in less regulation?

The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) reports that since 2009, drug overdose deaths have overtaken those from motor vehicle crashes, and the trend has continued since then. In 2013, drug overdoses were the leading cause of injury death claiming 43,982 lives, nearly three times as many people as homicides. Of those drug-related deaths, 22,767 (51.8%) were from prescribed drugs, more deaths than from all illegal drugs combined.

A majority of these lives were lost due to two classes of medications: opioids, also known as painkillers (e.g., OxyContin, Vicodin), and benzodiazepines, a class of anti-anxiety drugs (e.g., Xanex, Valium, Ativan). Opioids are by far the biggest offender:

- The CDC reveals that in the U.S., the cost of prescription opiate abuse was $55.7 billion, including lost workplace productivity, healthcare, and criminal justice

- Opioids were involved in 71.3% of all prescription medication overdose deaths in 2013

- Each day, 44 Americans die from painkiller overdoses, and in 2013, nearly two million Americans abused them

And yet, when asked about reasonable prescription limits in a PBS (2013) interview, a CDC representative reports that,

Very few states have laws requiring specific steps when exceeding daily dosage limits for all prescription painkillers…The existing limits do not place major constraints on prescribing.

Returning to the larger issue of high-volume prescriptions for all drug classes (not just painkillers), why is this happening? Two reasons: doctors are paid and patients are heavily marketed to.

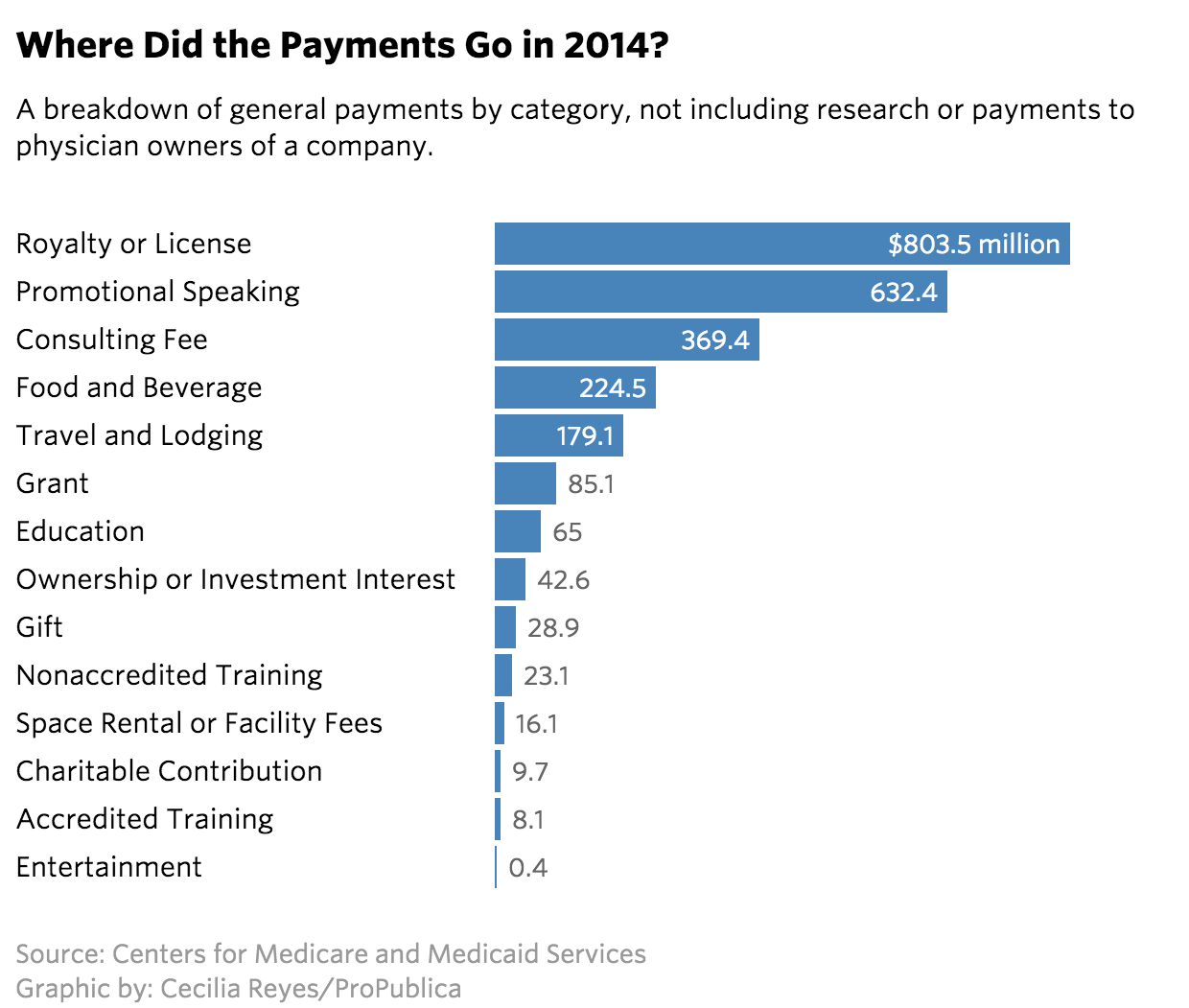

First, between August 2013 and December 2014, doctors received $3.53 billion for consulting, speeches, travel, and meals from pharmaceutical companies, and this is only in disclosed payments. ProPublica’s “Dollars for Docs” (2015) project tracks not only how much Big Pharma is spending to woo doctors, but also calls out the greatest offenders:

Second, it’s interesting that since 1997, pharmaceutical companies have been able to hawk antidepressants, diuretics, antipsychotics, anesthetics, muscle relaxants, corticosteroids, antihistamines, and boner pills, among others, all on television and public billboards as if they were benign deodorant or salad dressing. This isn’t the way it should be. Europe has banned this practice—also referred to as direct-to-consumer advertising—and it’s easy to see why: it’s widely abused. As the old saying goes, “Don’t make the doctor your heir.” In a similar vein, why would we let entities that profit from our sickness—real or imagined—sell drugs to us? There’s a clear conflict of interest between private enterprise and public health. Companies rely on making money, not on making people well, and it’s in their financial interest to convince people to take drugs. Plain and simple.

Every once in a while, Big Pharma receives a slap on the wrist and a small, modest bite is taken from their profits. GlaxoSmithKline had to pay $3 billion in 2012 for false advertising, paying kickbacks to doctors, and making misleading statements on the label, among other charges. Pfizer, Johnson&Johnson, Abbott Laboratories, and Eli Lilly have all had to pay settlements of over $1 billion in recent years on similar charges (Source: Wikipedia).

Despite all of this, the industry remains defiant and committed to increasing their profits. Bloomberg (2015) reports that there were 63 million prescriptions for ADHD drugs last year, with adults taking 53% of them. Shire’s Vyvanse, an amphetamine-derivative approved to treat both children and adults, celebrated an 18% uptick in sales last year and CEO Flemming Ornskov noted gleefully that in 2017, this drug will be used to treat binge-eating! Ornskov adds that, “Sweden is one of [their] fastest uptick markets, even beating the benchmarks for the U.S.” The use of drugs should not involve a desired “expansion of markets” at all. Manufacturing an ever-increasing pool of pill-ready patients is not in the interest of public health. This is the problem.

I can go on about the racial and socioeconomic biases of American drug laws; the alarming explosion of Americans taking pills; the increasing power of drug cartels in the face of punitive attitudes toward substance (ab)use; and even why a more accepting attitude toward marijuana use has been good for society. Instead I’ll close with some glimmers of hope. Here are my recommendations to ameliorate some of the damage done by the misguided War on Drugs (WoD):

- Decriminalize all drugs. Let’s take illegal drugs out of the shadows to disempower cartels, to save money on non-violent crime prosecution, and to get people with addictions the help they need. The Cato Institute has countless studies on the failed WoD, including an examination of the effects of decriminalization in Portugal, where drug use overall is decreasing, the government is saving money, and most importantly, people with substance abuse problems are treated as medical patients rather than social pariahs. There are countless indicators that the libertarian position on drugs is a strong one, and my clients at the non-profit clinic in San Francisco would have benefited greatly from time in treatment rather than time in prison.

- Ban direct-to-consumer advertising for Big Pharma. The only people that should be telling us what to put into our bodies are doctors and nutritionists, not marketers.

- Appoint impartial doctors and scientists to lead regulatory agencies such as the FDA, not corporate insiders. This is a no-brainer. We need independent-minded experts with a commitment to safeguarding public interest, those who won’t be swayed by “old friends” or the sparkling arsenal of lobbyist treats from Pfizer, Merck, and all the others.

- Take care of your own mental and physical health and avoid relying on one-pill solutions. Of course there are medical conditions which warrant medication and surgery. I’m not Amish or a Scientologist, but I do believe that if Americans took more pride in being healthy, we’d all be better off. Less addicted, less sick, less judgmental, and happier.

Thank you for being so interested.