Overwhelming.

Exhausting.

Awful.

Hopeless.

What words come to mind when you think of 2020?

Many of us feel that this is one of the most difficult years in U.S. history—and it’s true. We are suffering from the mismanaged COVID-19 pandemic, which has now killed over 116,000 Americans, 39 times the death toll of 9/11. The murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis, among so many other black citizens, has activated massive protests against police brutality. We have a cowardly incompetent president, and the only tie that binds the public is our unmoored rage.

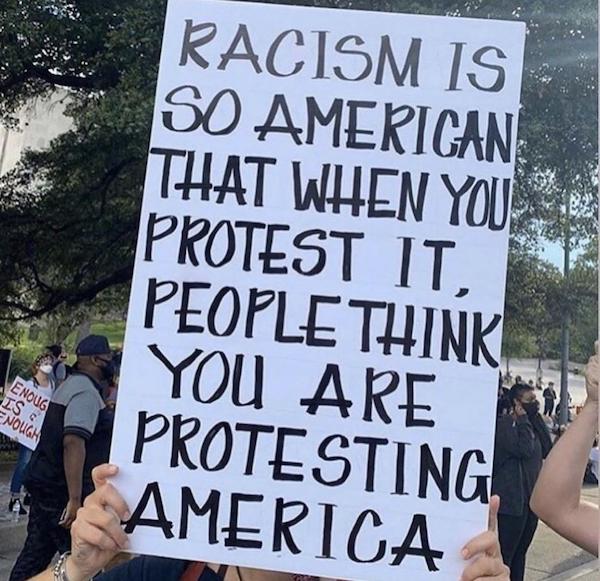

To the racist institutions in this country, white anger is righteous and black anger is frightening. Large white men with assault rifles can march on Michigan’s capital to intimidate the Democratic governor without a reaction from the police; on the other side of the political spectrum, peaceful protesters for racial justice have been kicked, trampled, beaten, gassed, and shot by the police all over the country. Curfews were enacted and Trump threatened to send in the military to “dominate” his own country’s cities.

When it comes to race, we have always been at war with ourselves. The devastating legacy of slavery has fed inequality in education, housing, criminal justice, and law enforcement, not to mention the daily indignities of individual prejudice. Until a white person experiences fear while jogging, playing video games at home, or walking and eating skittles, we cannot pretend to understand what it feels like to be constantly surveilled and over-policed for our skin color.

Our collective discomfort and anger over racial injustice were long-overdue in the U.S. Although the Black Lives Matter movement felt dormant to white America in between the most egregious murders, we’ve reached a tipping point: millions of us have decided that doing no harm on the basis of skin color isn’t enough. We’ve embraced a new era of anti-racism, in which bigots are rightfully outed and fired from their jobs.

A friend of mine told me that we’re living in “cool times”—an era that feels like hell on the ground but in retrospect will be considered pivotal in making progress. As uncomfortable as we all feel right now stewing in our rage and despair, I’m inclined to agree.

In fact, while the entire Trump era has been excruciating, the backlash to his lack of character has helped bring about important changes in American society. There has been a major international protest every year since he took office: the Women’s March (2017), the March for Our Lives (2018), the School Strike for Climate (2019), and the powerful resurgence of Black Lives Matter (2020).

It started with the Women’s March in 2017, the day after Trump was inaugurated. I was in Washington DC, and people protested in cities across the world in a powerful display of anti-sexist unity. The #MeToo era followed shortly, and a cascade of hideous and powerful men lost their jobs—many of them replaced by women.

While 1992 was branded the “Year of the Woman” when a four new female senators were elected to the U.S. Congress, the Blue Wave of 2018 brought 148 women into Congress, as well as six female governors.

This represents real progress.

A year later, a young man killed 17 students at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida. A new student-led protest against gun violence was born. Nearly two million Americans marched in 900 cities across the U.S. and there were companion events across the world. The March for Our Lives became one of the largest protests in U.S. history, and it had a lasting impact on legislation: in 2018, 67 gun safety bills were signed into law across 26 states and Washington DC.

In 2019, the School Strike for Climate took shape. What had started in Sweden with an exceptional young woman, Greta Thunberg, became an international movement to take on the fossil fuels industry and protect our planet for future generations. There were large international protests in March, May, September, and November—all of them drawing millions of people into the fight to protect our world from global warming. September’s “Global Week for Our Future” event drew more than four million protesters and is hailed as the largest climate strike in world history.

And here we are now, confronting the shameful and enduring legacy of slavery in the United States. Racism in our institutions and citizens stems from our failure to confront this country’s festering wound: our nation’s wealth was built on the backs of African American slaves, and their descendants have barely shared in that prosperity.

When the black community has accrued wealth, whites slaughtered them, as they did in the Tulsa Massacre in 1921, which devastated Black Wall Street. Most Americans hadn’t heard of this genocide until the graphic novel Watchman was turned into an HBO series. Our history books tend to gloss over white violence within our borders.

But this has begun to change. Michael Brown Jr., Philando Castille, Walter Scott, Sandra Bland, Tamir Rice, Eric Garner, and now George Floyd—among so many others—are household names. A majority of Americans are horrified by the ongoing brutality against our black citizens. And beneath the rage at the root of our American wound, we’re beginning to see some signs of healing.

The Minneapolis Police Department has been defunded in favor of more communal-minded actions, which address access to basic services. Charges are being filed against police officers across the country, and some have been arrested for their violent handling of protesters. Black Lives Matter murals are popping up on large avenues across the nation. Powerful businesses have stood up in solidarity with the BLM movement; Twitter, Nike, and the NFL have declared Juneteenth a company holiday. Even NFL Commissioner Gooddell has softened his stance on kneeling during the national anthem. This is a large step for a conservative white-owned institution, which denied activist Colin Kaepernick a job for taking a knee in a peaceful protest against police brutality.

In the same way the #MeToo movement cost countless assholes their jobs, racists are now being called out publicly. In May, Amy Cooper invoked her white privilege and threatened to lie to the NYPD about “an African American threatening her life.” Christian Cooper (no relation), the black man, is a Harvard-trained writer and editor who enjoys birding. His crime? Asking Amy to leash her dog in Central Park. For her racist lies, she lost her job as a VP of an investment firm.

In Eugene (where I live), local business owner Paula McGuigan has been called out for her racism and insensitivity. She posted an appalling photo of her kneeling on the neck of a man with the bizarre caption “Ready for my Minnesota trip…#asianlivesmatter.” Her business, Home Spray Foam and Insulation, was flooded with so many one-star reviews that Yelp had to flag the “unusual activity.” She issued an apology, but the damage is done: you can’t get away with this racist shit anymore.

Perhaps most importantly, white people across the country are opening their eyes—many of them for the first time—to the systemic racism that has plagued the United States since its founding.

Some white people have been calling their friends of color and asking how they can be better allies. While these efforts are made with good intentions, the reactions have been mixed. After receiving a deluge of messages from white people in his life, a friend of mine quipped that he was “seriously considering hiring a virtual assistant and asking white friends to pay for it.” I can appreciate this sentiment, especially since it’s not the black community’s job to educate us—we have to listen and do the difficult work ourselves.

As clumsy as white Americans’ efforts can be, I still believe that the majority of us want to overcome personal prejudice and dismantle racist institutions. The media tends to amplify examples to the contrary—the Charlottesville racists, the MAGAts, our goddamn ignorant POTUS—but that braindead megaphone can’t drown out the millions that protest today.

There’s no single handbook for becoming “woke.” It’s a daily decision to rethink our implicit biases. It’s a desire to throw our bodies on the gears of the system—our roads, our workplaces—and demand the overhaul of racist institutions such as law enforcement. It’s a recognition that our racism at home is interwoven with our imperialism abroad; without stoking the white American fear of immigrants, non-Christians, and people of color, our bloated military wouldn’t be able to invade the Middle East for oil or Vietnam and Venezuela to “defeat communism.” Considering citizens of these countries as less-than-human—that peculiar and twisted racism—drums up support for these bloody colonial injustices.

So how can white Americans confront their privilege and better understand how racism operates? Seeking out the experience of being the minority in a group is a valuable tool, whether it’s living abroad with an unfamiliar culture and language or volunteering in a different community. I lived in Niigata, Japan for two years, and the daily reminder that I was “the other” opened my eyes more than any book could. Growing up in a predominantly white city, I had a lot of blind spots that my Berkeley education in sociology and psychology couldn’t remedy. And I still have work to do.

When you are the only member of a visibly identifiable group—a person of color in a white community, a woman in a room full of men, a trans woman among those who were born with female bodies—you’re both hyper-surveilled and invisible. People might stare or get uncomfortable in your presence, but they also might ignore or exclude you, not knowing exactly what to make of you.

This lonely discomfort is useful and calls into question what we take for granted being in more homogenous groups. It helps build empathy for those unlike us—and a friendly curiosity of cultures unlike our own. Exposure to what was once foreign helps to allay deep-seated fears and can build mutual respect.

I acknowledge the limitations of my experience. I cannot change my 0.1 millimeters of white epidermis, but I know this: people are mostly good everywhere in the world. And when we approach unfamiliar groups without judgement and with an open heart, everyone benefits.

So let’s embrace the mass discomfort of 2020. We’re living in “cool times” and in retrospect, we’ll realize how instrumental this prickly awareness of sexism, gun violence, climate change, and racism has been for us to advance. The work is just beginning, but our rage, anxiety, and sadness are symptoms of outgrowing old ways of thinking and conducting ourselves.

And that gives me hope.

Thanks for seeing the good in what has truly been a “terrible, horrible, no good, very bad” year. You give your readers hope.